Imagine this: you’re leading a team of developers and designers on a project. You notice that some of them have a hard time keeping up and make mistakes, but you don’t know how to communicate in a way that will not embarrass them and separate them from the team. In the end, you miss the deadline, the client is furious, and everyone is blaming each other.

Not giving feedback or not providing it effectively can lead to serious problems. Projects can fall apart, team morale can go down, and even relationships can suffer.

In this article, our expert has collected the top tips on how to give feedback, what the 10 do’s and don’ts of getting your point across, and how to receive feedback professionally.

What is Feedback?

Before we go any further, it’s crucial to quickly discuss the most important concepts:

- Feedback: a neutral expression that includes both positive and negative

- Constructive criticism: negative feedback, focuses on issues that need to be fixed

- Praise: positive feedback, focuses on the part of the work that turned out well

Now, that this is out of the way, let’s see why giving feedback is crucial, and how to give feedback that uplifts and helps the other person grow.eet the company’s business objectives and satisfy the end users. Experienced professionals understand this, but newcomers should be reminded again.

Why Giving Feedback is Important

In the IT sphere, everyone is familiar with the concept of performance review, which has many nuances: how to successfully select the moment and consider all the subtleties in giving feedback. And if you are not yet in IT, but would like to experience a performance review yourself, check out our IT jobs, and join our team!

Here are a few reasons why giving effective feedback is important:

Unite the team and build trusting relationships

Well-organized and systematic feedback, in a friendly atmosphere, improves team interaction and employee engagement. And where there is sincerity and trust, it’s easier to find common ground with different people and achieve your goals together. This is what they call a healthy feedback culture in the corporate world.

Get an excellent final result

The fundamental goal is to do a quality job to make a good product for all customer requirements. If you deliver feedback containing an analysis of the mistakes made, you help the specialist understand what to focus on in the future.

Train newcomers and develop the team

Just pointing out mistakes is not giving feedback. “Don’t do this, do that” doesn’t work. Be sure to explain why their work is not what you want. This is the only way for a person to learn from their mistakes and grow professionally.

What is Effective Feedback?

Feedback can be considered effective if it brings long-term results.

Either a positive comment that motivates the receiver even more, and builds their confidence. Or constructive criticism that changes their way of working and helps them fix their mistakes, and grow.

At the end of the day, effective feedback is always positive because if delivered right, even a critique should be uplifting and helpful.

How to Deliver Effective Feedback

Providing feedback should be regular and timely. The frequency depends on each specialist’s knowledge level and the project’s complexity. Perhaps the client himself often makes changes to the terms of reference, and this affects the work of the entire team.

Then there is a need to be constantly in sync at individual stages of the work. Or the client wants to see intermediate results more often. In this case, you agree on the frequency of feedback with the client and then communicate directly with the work performers.

Common reasons for giving feedback:

- There is feedback from the client about the quality of work of a particular specialist

- There is a request for feedback from the specialist with a demand to evaluate his skills, to advise on the further development

- The supervisor notices something that needs to be discussed with the team or the client

Feedback is not just for fixing specific performance problems. Well-deserved praise motivates a person and helps him believe in his abilities. You can point out errors in one area of the project and say nothing about another site, and then it is clear that everything is fine there.

However, it’s not evident to everyone, so it’s better to spell out the benefits, especially for beginners. Great feedback can improve performance fast. So, let’s talk about how to deliver feedback effectively!

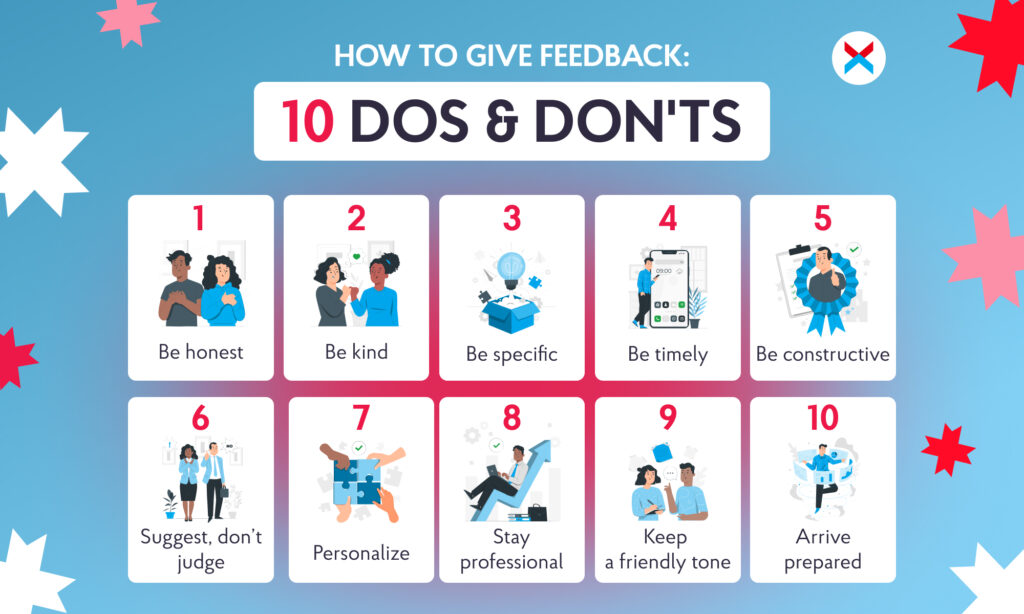

How to Give Feedback: 10 Dos & Don’ts

- Be honest: Kind lies can bring harm in the long run. If you see a mistake don’t hide it, or think they will notice by themselves and fix it later. Let them know early on, so they can learn from it, and grow professionally. Don’t try to spare their feelings!

- Be kind: Being rude defeats the purpose. They will be resentful instead of grateful, and might not follow your advice. When giving feedback, remember, that everyone can make mistakes, and making them feel uncomfortable is not the goal.

- Be specific: Don’t say generic statements when giving feedback. Always point out the exact issues or solutions you want to discuss. That’s also why ad hoc feedback usually doesn’t work, you need to collect your thoughts in advance.

- Be timely: Don’t wait half a year to circle back because by then the damage has been done (if the mistake is big!), and everyone involved has already forgotten about the task.

- Be constructive: “I don’t like it” is an ineffective feedback. Share the reason why, and provide alternatives and solutions. When using the word “because” people tend to accept it more.

- Instead of negative words, use suggestions: Don’t say “mistake” or “wrong”. Focus on the solution “I think we should change this to that because…”

- Personalize the feedback: If you know the other person, you know how to talk to them. Use humor that they’d appreciate, and use their language. If they don’t speak such good English, use simple words. If they are not highly educated, make it easy to understand. Find a way to connect with them.

- Stay professional: Always focus on the project, and not on their personality. Don’t say “You are good”, rather say “Your quality of work is great” or “The way you handled this issue was inspiring”.

- Keep a friendly, respectful tone and attitude: Even if you are personally not close, giving feedback can be a good experience for both sides, if you maintain a nice atmosphere.

- Prepare for the feedback conversation and keep it private: Collect data, take screenshots, and write bullet points. Giving feedback face-to-face can get messy quickly. Your notes will keep you on track, and you can also share them afterward as written feedback, and a summary of your meeting. And if you provide feedback for one person only, don’t do it in front of the entire team.

How to Give Feedback That’s Negative in a Constructive Way

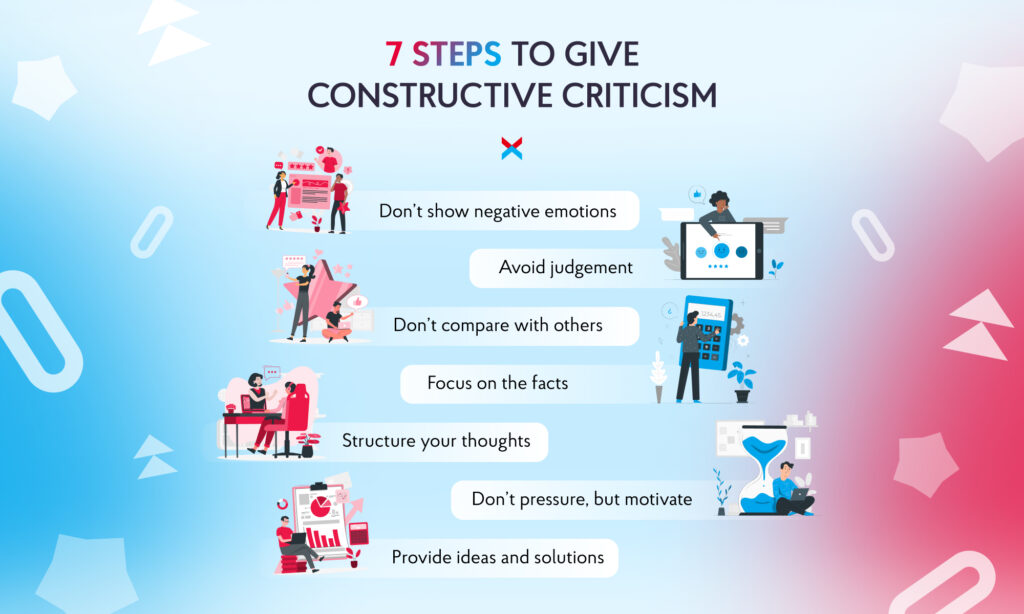

As a mentor or supervisor, you should consider these key points when giving constructive criticism:

- Don’t show negative emotions. When giving feedback, you should avoid showing overwhelmingly negative emotions, like frustration, anger, or disappointment. Pay attention to your body language and words! It is worth distinguishing between one’s attitude towards a person and their work.

- Avoid judgement. As a feedback giver, it is unacceptable to be prejudiced against an employee because of their reputation. Always evaluate a specific project, task, or reporting period.

- Do not compare a person with other team members. Especially specialists of different levels and experience. This deprives your feedback of value in the eyes of others.

- Give feedback based on facts. Base your review on clear facts and arguments that can support your assessment. To do this, look at the employee’s past projects, and recall his achievements, failures, and how he managed to improve his work. You usually have the last two or three weeks of work in your head, but for quality feedback, you need to assess the progress of, let’s say, six months.

- Provide feedback that’s structured. Think through the outline of the conversation and identify anchor points. Short feedback will not reveal all the details, but too much information just can’t be well received, so look for a balance in the volume of feedback.

- Give feedback and not stress. Don’t pressure the specialist and do not impose your opinion, don’t scold or blame the person.

- Provide ideas and solutions. If the specialist doesn’t know how to deal with the issue, tell them exactly what to change. Give them actionable feedback, a direction, a tip, or anything else they need.

The purpose of your conversation is to help the specialist become the best, to inspire and motivate them. Create a comfortable environment for the discussion.

Here are a few examples of how to give feedback:

“I think you should pay attention to…”

“Try to improve such things…”

“I noticed that this project is progressing slower than expected. Is there a reason why you don’t feel motivated? Is there anything I can help you with?”

Giving effective feedback means teaching a person to analyze his work correctly and better understand the essence of the problem.

Constructive Feedback Examples and Feedback Techniques

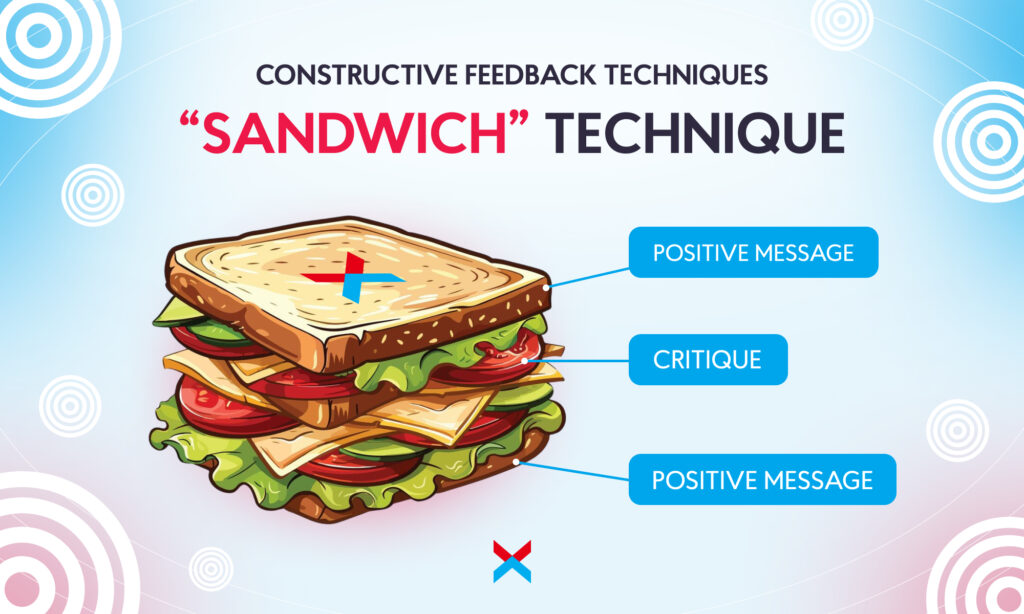

The “sandwich” feedback technique

And now, let’s pay attention to a few techniques to help you formulate your feedback constructively and without value judgments. There is a popular model called the “sandwich rule.”

According to this model, giving feedback has three steps:

- An initial positive message. Highlight the good things about the person’s work, even minimal successes, and start with positive feedback. This will show that you recognize their efforts and put the employee in a good mood for further conversation.

- Critique. In the central part of the constructive feedback, identify the problem areas and those that need to be improved.

- Motivational positive message. You should conclude the conversation with specific suggestions on how the person can do the job better. Express confidence that this task is within the specialist’s power and that he is on the right track.

Here’s an example of giving effective feedback with this technique:

“The project is going great, your time management skills are amazing, and the client is also very satisfied with the results. As we move forward, I’d like to discuss this and this part in more detail.

We noticed a few bugs, and it is better to be prepared in advance, so I suggest this and that. What do you think? I’m sure, you can handle the extra tasks with confidence.”

Important: Some experts say that this technique is already outdated. While the basic idea is good, there are a few issues when you deliver feedback with this structure:

- Some people don’t notice the critique and think that all is great

- Others feel that the praise is fake because there is always a big BUT coming

If you keep a healthy balance and remember to be sincere and not sugarcoat it, this technique can still work well in a feedback session.

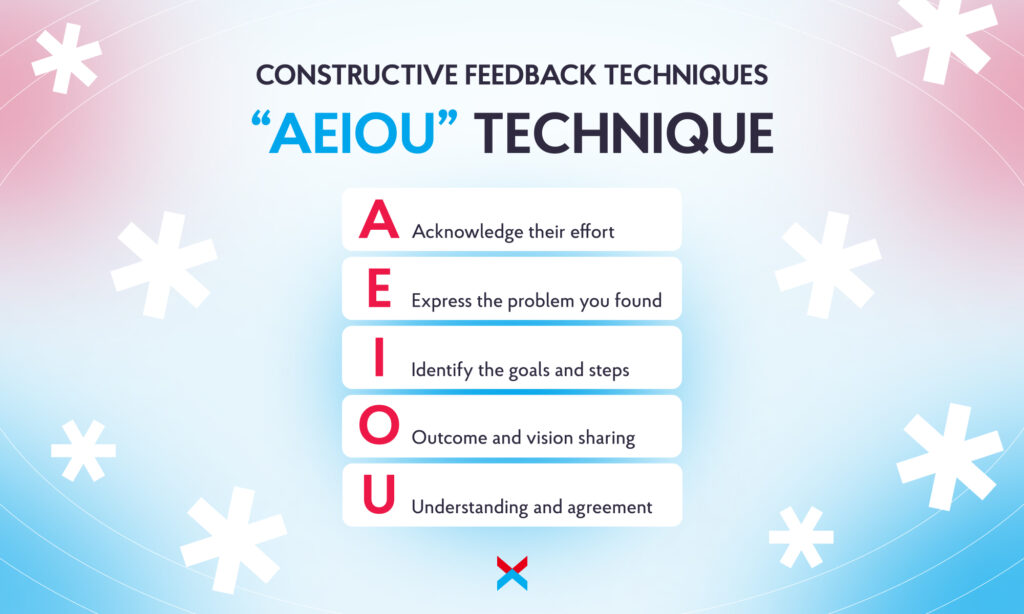

The “A-E-I-O-U” feedback technique

Another interesting approach when giving feedback is A-E-I-O-U. This acronym stands for the concept of positive intentionality: the understanding that you want to help, not confront. This can help you give better feedback and is more sophisticated than the previous technique.

This approach can be used as a communication plan:

- A – Acknowledge their effort. In the beginning, identify the positive desires of the employee and voice them: “I know you are trying hard,” “I see that you want to perform the task as best as you can,” etc.

- E – Express the problem you found. Begin with a phrase like, “I am concerned that…”. Only rely on examples of the work done.

- I – Identify the goals and steps. Set the goals and map out the way to get there. Your instructions for corrections must be specific and unambiguous.

- O – Outcome and vision sharing. After describing the desired amendments, share your vision of the result with the specialist. Mention the possible benefits of achieving a successful outcome for everyone involved.

- U – Understanding and agreement. Finally, make sure the person understands you correctly. Allow the professional to give their vision for further action or alternatives, and reach a compromise.

How to Improve Feedback Delivery at Work

Giving feedback one-on-one

You can organize a one-on-one feedback session when it’s necessary, and when you know that you haven’t talked to a colleague in a while.

It also provides a safe environment to have an honest discussion without interruptions or judgement from others. Pointing out mistakes in a public feedback, in front of the entire team can be humiliating and build resentment.

On the other hand, praising the other person in front of the team highlights your appreciation. Always evaluate what the situation requires.

Paying special attention to Juniors and Trainees

You should talk to Junior specialists more often because they need more feedback and constant guidance. For example, providing feedback to novice designers is essential for their growth. Like, “It’s better to increase the font size here because it’s hard to read.”

Experts with experience will also understand the short “Think about the font; there’s a problem here.” In doing so, check the level of their knowledge.

How to Receive Feedback at Work

Last but not least, let’s talk about how to receive feedback gracefully – especially if it’s negative feedback.

- Don’t take it personally. This is the most difficult, but always approach the specific feedback from a perspective, that it is a criticism of your work, not you. Take a deep breath, and try to take the other’s perspective, or put on your objective lenses.

- Keep an open mind. You might not agree with the feedback right away but do spend some time thinking about it. In most cases, you will realize that there is some truth to it and can find a compromise.

- Stay polite, but firm. Thank them for providing feedback, and share your own professional opinion on the matter.

For example: “Thank you, I understand your point of view. However, in my experience, a blue CTA button has a better click-through rate than a red one. I can show you the numbers, and then we can find a solution together.” - Let it go. In most workplaces, the final word is given by a higher-up, who may or may not agree with you. Don’t start a fight or argument over something small. Always share your point of view, supported by numbers and facts, but if you “lose”, just move on with their requests.

Extra tip: As an employee/freelancer, always collect positive feedback! You can show these positive reviews in your Portfolio, and use them as proof of your quality work. Always ask your managers and clients to share feedback with you!

It’s best to use screenshots, with the full name and position of the person showing – with their permission, of course. And if you want to learn more about applying for new jobs, find out what is a good skill to put on a resume!

Constructive feedback can also be useful in the future (beyond learning from it). In many job interviews, they ask you to explain a situation when you made a mistake, and how you solved the issue. Collect a few examples, so you are ready for these questions!

Did you like our article? Contact us to leave your feedback! 😉